Gustav Mahler

* 7 July 1860 Kaliště u Humpolce† 18 May 1911 Vienna

During his life composer Gustav Mahler was regarded mainly as a brilliant opera conductor, known in particular for the periods when he led the Vienna Court Opera and the Metropolitan Opera in New York. His legendary pronouncement “My time will come” (Meine Zeit wird kommen) started to become reality during the 1960s and especially the 1970s. Mahler’s symphonic works and Lieder first gained recognition through conductor Leonard Bernstein (who completed the first complete stereophonic recording of all his symphonies and performed them in Europe) and definitively achieved widespread popularity thanks to the film Death in Venice, in which director Luchino Visconti used the music of the Adagietto from Mahler’s Fifth Symphony.Mahler, a contemporary but also to a considerable extent a rival of Richard Strauss, closes and recapitulates the great era of Central European Late Romanticism and at the same time inaugurates the modern age, in which his works point to such contrasting personalities as Arnold Schoenberg (and the whole Second Viennese School) as well as Dmitri Shostokovich and many other 20th-century composers including Krzysztof Penderecki.

Mahler′s works bear the traces of a whole series of influences and inspirations from the Czech cultural milieu with which from his childhood and youth the composer had quite a number of connections and contacts. In certain places where he was engaged, he also introduced Czech works, especially those of Smetana (Dalibor, The Bartered Bride), whom he admired and whose works he knew. It was Prague that on 19 September 1908 heard the world premiere of Mahler’s Symphony No. 7 performed by a hundred-member orchestra made up of members of the New German Theatre and the Czech Philharmonic and conducted by the composer himself. From the very start in Prague and Czech cultural circles, Mahler’s works were received very favourably, one factor here being that he was considered a fellow countryman by the better critics. Thus there was created a local tradition of Mahler interpretation interrupted in essence only by the Nazi occupation. Zdeněk Nejedlý was the author of one of the first monographs that appeared immediately after the composer’s death, and one of the most important propagators of Mahler’s works was conductor Václav Neumann.

Gustav Mahler was born in the little town of Kaliště u Humpolce in a Jewish family on the Czech-Moravian border, and he grew up in the supranational milieu of religious and linguistic diversity of Jihlava, where both his parents are buried in the Jewish cemetery. He received a thorough education in music at the conservatory in Vienna, where he went to study in 1875. Only two of his school works from that period have been preserved: the first movement of a Piano Quartet in A minor and a fragment of a Scherzo in G minor. After his studies Mahler worked as a band leader and conductor in the provinces and little by little in the larger theatres of Austro-Hungary and Germany of that time: Bad Hall (1880), Ljubljana (1881 – 1882), Olomouc (1883), Kassel (1883 – 1885), Prague (1885 – 1886), Leipzig (1886 – 1888), Budapest (1888 – 1891) and Hamburg 1891 – 1897). His life and conducting career reached their high point during two periods: first, the decade when he was director of the Vienna Court Opera between 1897 and 1907, a position he was forced to give up because of the growing anti-Semitism (even though he had converted to Catholicism before taking on the position of director) as well as because of his insistence on the highest standards; and later, during his tenure in New York at the Metropolitan Opera (1907-1911). Gustav Mahler came to a very tragic end. On top of his own heart problems and the death of his daughter Marie (12 July 1907), there was added his feeling of loneliness and a serious crisis in his marriage. His relationship with the 19-year younger Viennese beauty Alma Schindler gradually began to break down, finally prompting Mahler on 26 September 1910 to visit Sigmund Freud.

Mahler composed most of his works during his summer holiday months in three places in the Alps: Steinbach on the Attersee, Maiernigg on the Wörthersee and in Toblach (today Dobiacco in Italy). The bulk of the composer’s work is formed by his nine extensive symphonies and his unfinished Tenth Symphony, his early cantata Das klagende Lied and Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of the Earth), a vocal-instrument epilogue to texts from old Chinese poetry, in which the composer bids a moving farewell to life. It may be of interest that the composer completed this work on the territory of what is now the Czech Republic, in Hodonín, on 17 September 1909. In his symphonic works Mahler often used forms with numerous movements, also using texts and vocal sections. Except for the Fourth Symphony (in four movements, the most “classical” although even here with a soprano solo in the fourth), his symphonies are characterized by extensive instrumental forces and their polyphonic conception – the liberation of individual voices or layers, a method somewhat like film editing, more typical of modern advances in the twentieth century. Also characteristic is his use and synthesizing of the bugle calls and “street corner” nursery tunes that Mahler had heard in his childhood with elements of the German-Austrian “Viennese” music tradition (including in the broadest sense of the term Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Bruckner and Wagner) – in particular, his joining of “high” and “low” art, something for which the composer in his own time was frequently criticized.

One of Mahler’s most frequently performed symphonies is the First Symphony in D major of 1888, a four-movement work with in the third movement the funeral march on the motif of the round “Frère Jacques.” Each of Mahler’s symphonies bears within it some great philosophical and intellectual message, the clearest of these perhaps being his Symphony No. 2 “Auferstehung” (Resurrection). Its closing movement with a text by Friedrich Klopstock (the first five lines) and mostly by Gustav Mahler is a special synthesis of the composer’s opinions on the meaning of our lives and whole being, a kind of synthesis of the Judeo-Christian and above all of the humanistic view of mankind: “Everything that is created must perish, but everything that perishes must rise again! There is nothing in this world without some meaning. Let us cease from trembling and prepare ourselves for something that goes beyond us, that lasts eternally.” In Urlicht in the fourth movement of his Resurrection Symphony, Mahler uses a text from the collection called Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Boy’s Magic Horn) published by Clemens Brentano and Achim von Arnim between 1805 and 1808. And in two other symphonies Mahler was to go on to work with these texts: in the Third Symphony (where he also uses a text by Friedrich Nietzsche) and in the Fourth Symphony with the text titled “Das himmlische Leben” (Heavenly Life). The Fifth, Sixth, Seventh and Ninth Symphonies were purely instrumental. We see a kind of exception in the Symphony No. 8 in E flat major, which has come to be known as the Symphony of a Thousand (the epithet in fact comes from Mahler himself): it is a two-movement work, and the author of Veni creator spiritus, the text used in the first part, is Habanus Maurus while the author of the text in the second part is Goethe (the final scene of Faust). The premiere of this symphony on 12 September 1910, which had been preceded by an extensive publicity campaign, represented for Mahler one of the greatest triumphs of his life. The acclaim for the work was extraordinary.

The genre of song constitutes the most important and indeed an absolutely essential role in Mahler’s creative work. Clearly, it often forms a kind of cellular foundation which permeates the whole symphonic tissue. In some cases the author of the texts was Gustav Mahler himself, in the case for example of the Lieder eines fahreneden Gesellen (Songs of a Wayfarer) of 1896. Quite frequently the songs are inspired by texts from Des Knaben Wunderhorn and the poetry of Friedrich Rückert (e.g., Kindertotenlieder – Songs on the Death of Children).Mahler’s music and his message have in the early twenty-first century become ever more appealing to his audience, forming with their content and their intellectual and emotional charge something like an unexpectedly relevant opening into the post-modern epoch.

Author: Jiří Štilec

Nejposlouchanější

Jiří Karásek: Muž, který zásadně mluvil pravdu. Hvězdně obsazená detektivní tragikomedie z roku 1965

-

Umberto Eco: Foucaultovo kyvadlo. Napínavý příběh tajemných spiknutí, nebo úvaha o realitě a fikci?

-

Svatopluk Čech: Výlet pana Broučka do 15. století. Ke 180. výročí narození autora

-

Jaroslav Rudiš, Petr Pýcha: Salcburský guláš. Temná místa minulosti dvou přátel vybublají na povrch

-

Martin Ryšavý: Tundra a smrt. Dobrodružná výprava k neprobádaným končinám lidské existence

E-shop Českého rozhlasu

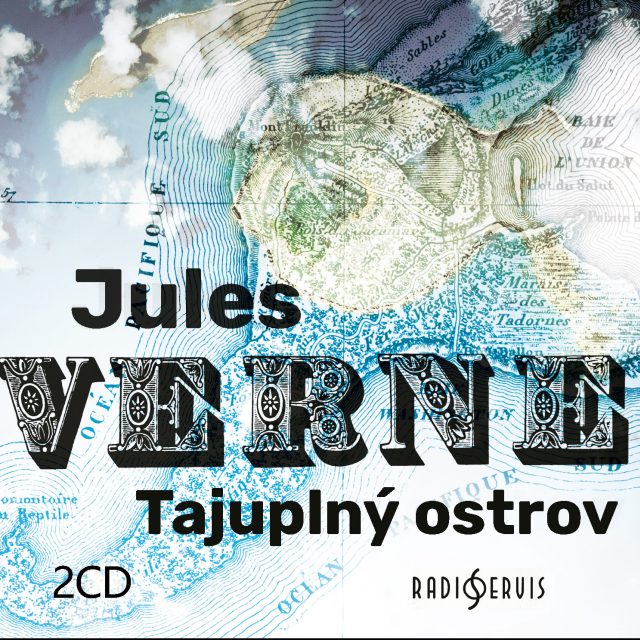

Vždycky jsem si přál ocitnout se v románu Julese Verna. Teď se mi to splnilo.

Václav Žmolík, moderátor

Tajuplný ostrov

Lincolnův ostrov nikdo nikdy na mapě nenašel, a přece ho znají lidé na celém světě. Už déle než sto třicet let na něm prožívají dobrodružství s pěticí trosečníků, kteří na něm našli útočiště, a hlavně nejedno tajemství.