Mikuláš (Nikolaus) Kraft

*14 December 1778 Esterháza in Hungary†18 May 1853 Cheb

Nikolaus (Mikuláš) Kraft was born on 14 December 1778 in Esterházy, where his father, Anton (Antonín) Kraft, played in the local orchestra. Godfather to the new baby was Prince Nikolaus Esterházy himself. As the son of a cellist, he was from very early childhood led to music. He is said already at the age of four to have learned to play the viola, which he held between his knees like a cello. At six before an audience of aristocrats he played on the cello a little composition which he father had written for that occasion, and at eight Nikolaus received from Prince Esterházy a promise that he would be employed in his orchestra. After two more years of remarkable progress on the cello, Nikolaus accompanied Anton Kraft on a concert tour around Europe. They visited Vienna, Pest, Berlin and Dresden, and everywhere the younger Kraft was warmly received, and his artistry was admired. In accordance with his father’s wishes, however, he was given a more general education instead of more technical training on the cello; still, at eighteen, he was already devoting himself exclusively to music.

In 1796 he joined the Lobkowicz orchestra, where his father was concert master, and was appointed chamber virtuoso. It is probable that at period he subsituted for his father in the Schuppanzingh Quartet, which no longer had a stable make-up and in which even Prince Lichnovský sometimes played second violin. In January 1801 at his own expense Prince Joseph Lobkowicz sent the twenty-two-year-old Nikolaus off to study with the renowned cello virtuoso and teacher Jean-Pierre Duport in Berlin. Jean-Pierre Duport (1741-1818) had been engaged as concert master in the Prussian Court Orchestra in Berlin since 1773 and after the coronation of King Friedrich Wilhelm II was named chief intendant of Royal Chamber Music (1786). After a year of study, Nikolaus Kraft returned to Vienna in 1802, but on the way back he organized a concert tour through Holland. Prince Lobkowicz was not happy about this behaviour and ordered Kraft, as a member of his orchestra, to end the tour and return immediately to Vienna. Nikolaus Kraft obeyed but along the way still could not resist giving concerts in Leipzig, Dresden, and Prague. After his return, on 17 April 1803 in Vienna, the twenty-four-year-old Nikolaus Kraft married Katharina Grieshofer and continued to be active in Vienna as chamber virutoso in the Lobkowicz orchestra until 1809 when he assumed the function of solo cellist in the Viennese opera orchestra of the Kärtnertor-Theater. He did not however break off his relations with the House of Lobkowicz. Besides his work as an orchestral and chamber musician, Nikolaus Kraft performed as soloist and in addition to the standard repertoire also played modern compositions: for example, on 5 March 1809 he organized in Vienna a concerto academy, at which he performed among other works the world premiere of one of the most famous cello compositions, Ludwig van Beethoven’s Sonata for Piano and Cello in A major, Op. 69. The piano part was played by the German pianist Baroness Dorothea von Ertmann (1781-1849).

In view of the frequency with which such concerts were organized, Prince Lobkowicz started feeling jealous of his chamber virtuoso and offered to pay him a lifelong income on condition that without the Prince’s permission he would give concerts nowhere but in his palace. In fact, however, in the end this agreement never went into effect, for after his financial crash in 1811 the Prince was put under trusteeship. And so Nikolaus could continue giving solo concerts with no restrictions. In 1812 he performed at the French Ambassador’s and in 1814 he appeared at the Congress of Vienna. There he was heard in performance by King of Würtenberg, who offered him the position of concert master in his orchestra in Stuttgart. Nikolaus accepted his offer, bid farewell to his parents and siblings, and at the end of that year with his family left Vienna and joined the court opera in Stuttgart, where he was engaged for fully twenty years, from 1814 until 1834. During that period he also continued to organize solo concert tours.

In 1818 he undertook an especially noteworthy tour of the Rhein region with Austrian composer and pianist Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837), who had before that been active as Haydn’s successor in the function of Kapellmeister of the Esterházy orchestra in Eisenstadt (1804-1811). Then from 1816 to 1819 Hummel held the position of court Kapellmeister in Stuttgart, where he came to know Nikolaus Kraft personally. It may also be of interest that Johann Nepomuk Hummel was exactly one month younger than Nikolaus Kraft (Johann Nepomuk Hummel was born on 14 November 1778). They ended their joint concert trip in Hamburg, where Nikolaus Kraft met cellist Bernhard Romberg (1767-1841). Romberg esteemed Nikolaus Kraft very highly and gave a concerto for two cellos with him in Stuttgart two years after that (1820). As an expression of his admiration, Nikolaus Kraft dedicated to Bernard Romberg his first and second cello concertos. The third concerto was then dedicated to Johann Nepomuk Hummel.

While tuning his cello in December of 1834, Nikolaus Kraft suffered an incurable injury to his finger, this causing him to give up any further public performances. After an operation on his hand, he was awarded a pension on 1 January 1835, and that same year at the age of 57 he retired, continuing to live in Stuttgart until 1839. After the end of his concert career he devoted himself mainly to teaching music, especially to teaching the cello and composition, and most especially, to composing for the cello. He later moved to Saská Kamenice and from there in 1842 to Cheb or Františkovy Láznĕ. His daughter Vilemína and her husband Dr. Pavel Cartellieri lived in Františkovy Láznĕ. Nikolaus Kraft is thought to have died in Cheb on 18 May 1853 at the age of 75 (although the place of his death cannot be ascertained from public records).

Nikolaus Kraft was one of the most important cellists in the first half of the 19th century. A quotation from the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung of 1819 aptly describes his artistry: “Serenity joined with the highest degree of assurance and technical ability, the claraity and richness of every single tone on that difficult instrument coupled with studied and colourful bowing – these are the foremost qualities of this virtuoso. To those we might add nonchalance and a performance style that could serve as model because it rises above the usual affectation: it is refined and reveals informed good taste.”

Along with his career as a performer, Nikolaus Kraft also concentrated on teaching. The most outstanding of his pupils was Nikolaus Kraft’s son and the grandson of Anton Kraft, Friedrich Anton (Bedřich Antonín) Kraft. He was born in Vienna on 12 February 1807 during the period when his father and grandfather were members of Prince Lobkowicz’s orchestra. From his father and his grandfather he inherited a talent for the cello, and he concentrated systematically on this instrument and so excelled in this that already at fourteen he was performing in his father’s concerts. In 1824 he was admitted into the court orchestra in Stuttgart, where he played alongside his father. What became of him thereafter is not known. He died in Stuttgart on 4 December 1874.

Other of Nikolaus Kraft’s students included Joseph Merk (who also studied with Antonín Kraft), Heinrich August Birnbach (who went on to be a virutoso on the arpeggione, 1782-1848), and Bedřich Vranický (the son of Antonín Vranický).

In the first half of the 19th century Nikolaus Kraft’s works were promoted the foremost Russian solo cellist, Count Matvey Yurevich Vielgorsky (1794 - 1866). In his book Čeští violoncellisté (Czech Cellists) Bedřich Urie claims that Count Vielgorsky in his youth studied with the young Nikolaus Kraft and from him directly come to know his cello concertos which the Count then performed in his concerts – a claim that cannot be document although that the two met in Vienna is indeed quite probable.

As with his father Anton, Nikolaus Kraft’s compositions too were with few exceptions written for the cello. His oeuvre consists of virtuoso concertos, compositions for cello and orchestra, and duets for two cellos (concertos for cello and orchestra, divertimentos, boleros, fantasies, polonaises, potpourris, rondos, and variations); they amount to seventeen opuses. From his works that have survived, it has been possible to put together a list of his accessible works, most of which were published by the Peters publishing house. Works printed in Kraft’s time are today housed in the archives of Czech Museum of Music (part of the National Museum in Prague), in the Säschische Landesbibliothek in Dresden, in the Fürstlich Fürstenbergische Hofbibliothek in Donaueschingen, in the Bibliothek der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna, in the Archives of Czech Radio in Prague, and in the score archives of the Prague Conservatory.

For Nikolaus Kraft, composing was more like a complementary activity. He wrote mostly for “his” instrument. The most substantial part of his oeuvre is formed by his four concertos for cello and orchestra and a number of works of chamber character including what were in his time termed “salon pieces,” which traditionally highlighted the performer’s virtuosity and favoured melodious, somewhat sentimental expression: typical of salon style was the so-called Biedermeier. In this regard Nikolaus Kraft is a typical composer of his time – the time of a stylistic shift, in which the key expressive means of the old (in this case in particular some classicist melodic and structural mannerisms) were abandoned in favour of new means associated with early Romanticism.

Nikolaus Kraft entered a period of change when signs of a new style were forming, this coming on one hand from the activitis of the representatives of the rising “national schools,” and on the other hand with the intermingling of characteristic (or merely “attractive”) elements running counter to those schools. This is very typical if for example we compare the concerto works of period virtuoso-composers such as the violinists Paganini, Kreutzer and Spohr: on the one hand they were representatives of their “national schools” but on the other they were internatinally famous as virtuosos. With Nikolaus Kraft we are dealing with a marked type of early Romantic melodics which has its roots in the tunefullness of the Lieder genre (the Lied in that period had gained enormous social prestige);it is characterized by hightened expressivity both in its tendencies to both the dramatic and the sentimental (created mostly with the help of rather complicated harmonic means), by the use of the characeristic elements of the new kinds of dance (simple accompanying figures as one of the legitimat features not only of dance music but also of operatic and even concert music of early Romanticism). As with the works of his father, Nikolaus Kraft unequivocally places the emphasis on the virtuosity of solo performance, to which all else is subordinated although with a very solid overall artistic result. If we compare the musical impression made by the father Anton Kraft and the son Nikolaus Kraft, there is a striking resemblance, just as when one compares the composing styles of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart with that of his son, Franz Xaver Mozart, a case with an almost identical difference in age.

Author: Jiří Hošek

Nejposlouchanější

Džuniči Saga: Zpověď šéfa jakuzy. Syrový pohled do srdce japonského podsvětí a fungování tamní mafie

-

Anton Pavlovič Čechov: Višňový sad. Mistrovské drama s Tatianou Dykovou v hlavní roli

-

Mario Gelardi: Zlomatka. Tesařová a Myšička v italské hře o následcích jednoho coming outu

-

Paolo Sorrentino: Tony Pagoda a jeho přátelé. Poezie, vulgarita i něha v příbězích plných nostalgie

-

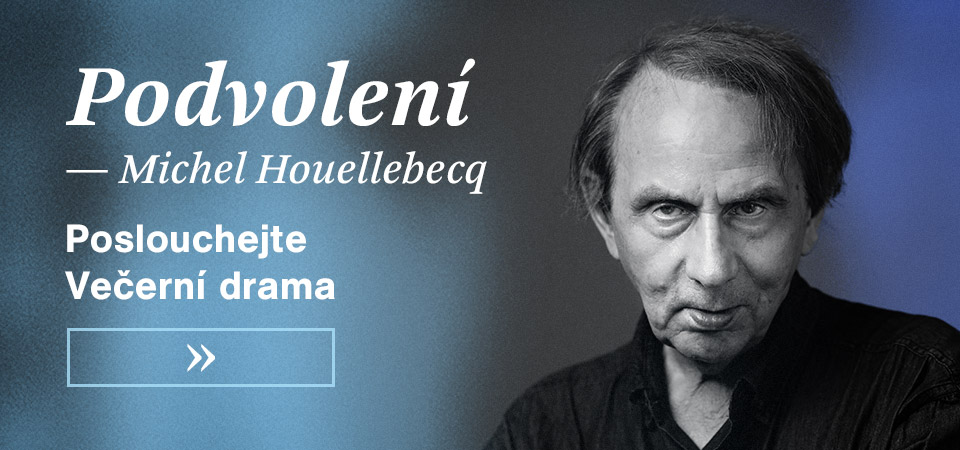

Michel Houellebecq: Podvolení. Francie blízké budoucnosti a příběh o hledání víry, lásky a hranic

E-shop Českého rozhlasu

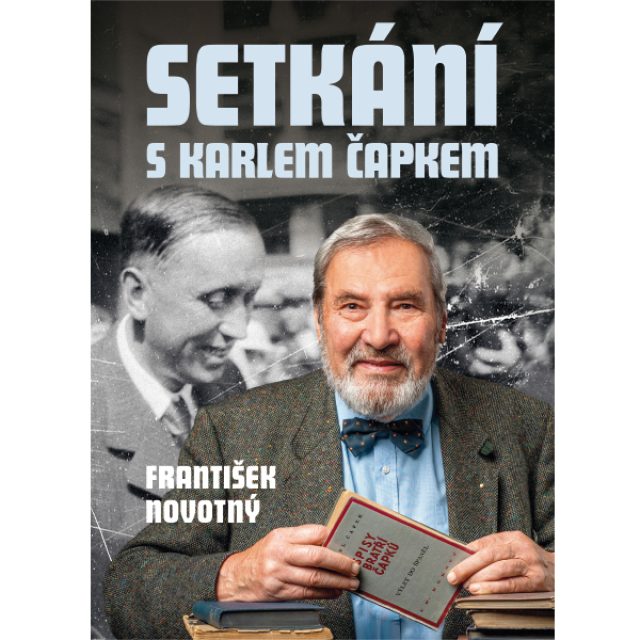

Přijměte pozvání na úsměvný doušek moudré člověčiny.

František Novotný, moderátor

Setkání s Karlem Čapkem

Literární fikce, pokus přiblížit literární nadsázkou spisovatele, filozofa, ale hlavně člověka Karla Čapka trochu jinou formou.