Josef Mysliveček, Il Boemo

* 9 March 1737 Horní Šárka (?) near Prague† 4 February 1781 Rome

Josef Mysliveček (also called Bisliweck, Melsiwesech, Misliwetschek, Metzlevisic, Mislivicheck, Misliwecek, Misliweczek, Misliwetzek, Venatorini) is considered by American musicologist Daniel E. Freeman (2009) to be “…one of the most talented composers active in the autumn years of the eighteenth century in Europe, …brilliant, successful and inventive.” His works include 28 operas, 8 oratorios, a number of cantatas, more than 50 symphonies, 29 overtures, 16 concerti and 134 chamber (instrumental) works.

His oeuvre exemplifies his repeated successful acclimatizations to new surroundings. According to an obituary published in Florence (17 February 1781), “…he was at nearly all the courts in Europe, where his abilities won him great praise and where he made friends with the greatest personalities.” If we look beyond the ongoing interest in his instrumental music, particularly in German-speaking countries (beginning in 1764), in Italy he experienced what was for a foreigner a vertiginous career as a opera and oratorio “Maestro Compositore,” ranking there until the 1770s among the most sought-after composers for the foremost opera houses and this in the face of strong competition. His works then found their way to Munich, Bamberg, St. Petersburg, Paris, Lisbon, Vienna, etc., even coming back to the Czechlands in the form of secular arias provided with new texts for performance in church, as we know happened with Mozart’s works a decade later. Mysliveček is an outstanding member of that series of Czech composers with ties to Italy -- Artophaeus, Černohorský, Seger, and Obermayer; and he is unquestionably the high point of the chapter on Italian opera in the Czechlands before Mozart.

The composer’s father, Matěj Mysliveček, “born in the Dub mill” in Šárka near Prague, was an Old Town burger, a miller at the Sova mill in Prague and the older officially sworn miller. Josef’s brother Joachym (1737 - 1788), who later supported Josef in Italy, was his younger twin “identical down to a hair,” the Old Town officially sworn miller, and the raftsman of Count Vincenc of Waldstein. His sister Marie Anna (1741 - ?) [S. Bernarda] entered the Cistercian order in Staré Brno. Mysliveček’s father with the prosperous traditional family trade of miller had relocated from the village of Horní Šárka to Prague, achieving the top position in the guild, where he strove “to root out old-fashioned harmful practices,” and gave close attention to the upbringing and education of his twin sons. Mysliveček spent his childhood in the Prague mills in Kampa and at the Old Town footbridge near Charles Bridge. After finishing the trivium with the Dominicans of St. Giles, a period of never completed study at the Jesuits’ gymnasium (“nihil profecit in logica”) and the private study of hydraulics with a professor Schorr, he entered an apprenticeship with Old Town miller Václav Klik. Along with his brother he was admitted to the guild (1758) and proclaimed a master (1761).

As early as 1749 Mysliveček way paying a “talented violinist,” and he studied counterpoint with František Habermann (1760), “who, apparently, however, went too slowly” (Pelcl), so that he went over to Josef Seger (1761), a former student of Černohorský. After half a year he was already composing symphonies, and he had six of them performed anonymously as it seems in the Waldstein Palace with the programmatic names of Januarius, Februarius, Martius, Aprilis, Maius, Junius. In this way he gained a patron, the music-loving Count Vincenc of Waldstein. Under the influence of Prague’s opera and oratorio production, he was drawn most of all to the composition of musical drama. The dedication and his subsequent personal performance of the cantata “a quattro” titled Il parnasso confuso as well as other sacred arias document Mysliveček’s continuing association with the Cistercians in Osek and with the Benedictines in Břevnov in Prague, who among other things lent him 3,000 florins when he set out for Italy.

Having already decided to leave, he rejected the settlement of a water rights lawsuit proposed by the Mladoboleslav city council (7 September 1763), left the family mill to his brother, and went off to work on recitative with Giovanni Battista Pescetti in Venice, the city with the greatest influence on the opera repertoire in Prague. There, however, he spent at most 17 months because after the publication of six symphonies by Haffner in Nuremberg (1764) he is already writing Count Waldstein a letter from Florence (1765) praising his only documented Czech student, Josef Obermayer, for his progress in composition. Neither Mysliveček’s stay in Parma in 1764, where according to František Martin Pelcl “he wrote his first opera,” nor that supposed work (Medea, 1764?) can be confirmed by any evidence, and indeed such claims do not fit in with the historical facts about Ferdinand Duke of Parma’s wedding. It is not then completely clear what opera led to those “most favourable reports” that caught the attention of the Neapolitan impresario Amadori: was it a reprise of Il Parnasso confuso (1665-1667) or of Semiramide riconosciuta in Bergamo (1765) or in Alessandria (1766). At the very latest by the year 1765 he had received the epithet “il Boemo” (although certainly not “il divino Boemo” which is a literary fiction of Arbes), compared to only two not authenticated later instances when he was given the sobriquet “Venatorini.” In Venice Mysliveček received more support from Prague after signing a promissory note to the Strachov Premonstratensians (1766). With the performance of a congratulatory cantata and the opera Bellerofonte in the Teatro San Carlo (20 January 1767) with Anton Raaf and Caterina Gabrielli as soloists, however, he entered the peak decade of his work (1767-1777). Crowned with the laurels of further successes in Naples and Turin, he returned after his mother’s death to Prague for the first time. Giuseppe Bustelli, director of the Kotzen Theatre, had his Bellerofonte performed during the carnaval season (1767-68) and began more systematic production of his successful Italian operas in Prague (Semiramide riconosciuta and Il Farnace in 1768). Nevertheles, what were usually repeated successes in Naples, Turin, Prague, Padua, Venice, Bologna, Florence, Milan, and Pavia were constantly accompanied by a lack of money, loans, and difficulties with creditors.Mysliveček’s friendship with both Mozarts dates from a meeting in Bologna (1770) but ended in 1778 because Mysliveček could not secure the contract he had promised for an opera after Wolfgang had been turned down in Naples. “He always lets me know when he needs my services,” wrote Leopold irately after he had handled business for Mysliveček in Salzburg and perhaps even recommended him for the position of Kapellmeister. It was indeed in this context that Leopold Mozart – and no one else besides him – pronounced the accusation of venereal disease (“Even if he could finally travel to Naples, how would that poor fellow look now in the theatre without a nose?...who can he blame but himself and his disgusting life?”). And yet the course of the disease as well as the method of treatment suggest he might have been suffering from quite different diseases (although the 1780 list of patients preserved in the Herzogspital in Munich does not so much as mention Mysliveček or his diagnosis); and even his alleged sexual adventures with Lucrezia Aguiari and Caterina Gabrielli cannot be proved. On the other hand, Mysliveček was recommended to Padre Martini both by Quirino Gasparini (“He composed an opera for the royal theatre in praiseworthy manner”) and by Anton Raff (“My dear friend Mysliveček...is known to be a person capable in his field and -- what I value most highly of all -- is considered to be a real honourable German [sic] which indeed he is”), as well as by the success of Nitetti in Bologna. Cardinal Lazzaro Opizio Pallavicini recommended that it be given repeatedly because of “...the worthiness of the drama and for the sake of the superb stage decorations of the production” on the occasion of a duke’s visit. After passing a test to be admitted to Bologna’s Accademia Filarmonica (1771), he used his fresh new title Maestro Compositore alla Forastiera as well as the designation Accademico Filarmonico. By 1771 he was enjoying the favour of an Englishman who had settled in Florence, Earl George Nassaw C. Cowper, who had been repeatedly elected president of the Accademia degli Armonici. Cowper’s orchestra conductor, Giovanni Schmid, bought arias and symphonies from Mysliveček (1774).

He maintained contact with Prague through an Easter oratorio sent to the Knights of the Cross at Charles Bridge. The Prague performance of La famiglia di Tobia (1770) is documented by a review in the magazine Die Unsichtbare. In subsequent years Adamo ed Eva (1771) and La Passione di Gesù Cristo (1773) were also performed. For the production of his oratorio La liberazione d’Israele on Good Friday (14 April 1775) a lavishly ornamented libretto weas even printed.

The Florentine newspaper Notizie del mondo often termed Mysliveček’s premieres unique in the response they provoked (“grandissimo incontro”), most often in connection with the independent ballets of composers, dancers and choreographers Charles Le Picq and Onorato Viganò. For Cowper’s accademia in the Casino della Nobiltà Mysliveček composed during the months of his treatment in Florence his oratorio masterpiece, Isacco, figura del Redentore (10 March 1776), considered by Freeman to be his best work of any kind. A year later Mysliveček stunned Munich with a revised version of this oratorio (for many years attributed to Mozart). Here the expanded instrumentation, the part of Gamari now given to a bass instead of an alto, the chorus of shepherds, and the march serve as evidence that he had accepted elements of Gluck’s reforms. Just as descriptions of costumes for the new version of his opera Ezio (Aethius), also written for Munich, have been preserved, so too have descriptions of the use of the instrumental marcia in operas and oratorios for dramatic effect. Those works as well as his only known melodrama, Theodorick und Elise, with a text in German, serve as proof of Mysliveček’s ability to react to the discussions about German national music (Hiller). One of Mozart’s letters documents the existence of a cantata for Munich titled Enea negl'Elisi, which is now lost; his cantata Armida has up to the present time gone unnoticed. Immediately after his departure from Munich, Mysliveček’s famous oratorio Isacco, figura del Redentore was performed by on Good Friday (17 April 1778) by the Prague Knights of the Cross with the Red Star although the personal attendance in Prague of “the famous gentleman Josef Mysliveček, il Boemo” cannot be proved.

After the death of the prince elector, the composer, now with his nose burnt off by “surgeons,” again travelled around the most important theatres in Italy. Contemporary news accounts refute the legend that Armida was a flop at La Scala in Milan because of Caterina Gabrielli’s pregnancy; in fact, the lady in question was a completely different Gabrielli! Only after this Armida in Milan (1779) did there appear in Rome a negative appraisal of “the famous MYSLIVEČEK,” one deriving, however, from issue taken with the garbled version “...of the works of the most famous of poets, he being the immortal Metastasio,” virtually the only librettist Mysliveček used. Serving to refute the incompetent opinion of retired officer Johann Wilhelm von Archenholz (“...everyone in Rome was of the opinion that they had never in that city heard such wretched music....”) are all the widespread copies of the aria “Luci belle, se piangete” from Medonte and the report in the Gazzetta universale of “the happiest success” and “the retention” of Mysliveček in Rome for an additional opera. But not even his final opera, L'Antigono (“which enjoyed great success”), could improve his financial situation, and he was forced eight times to borrow from the Monte della Pietà bank in Rome. An inventory of his estate confirms that he died in utter poverty in a pension in Rome in the street between Otto Cantoni and Strada del Corso. The inventory was drawn up at the orders of Cardinal František Herzán, Joseph II’s ambassador. His tomb in San Lorenzo in Lucina was paid for by a former pupil, an Englishman named Barry. His importance as a composer was recognised whilst he was still alive by a journalist at the Prager Intelligenz Nachrichten (1780), who among the “celebrated musicians in the Czechlands” alongside Stamitz, Gassmann, Benda, and Kammel, also names Mysliveček although he mistakenly believes him to be a conductor in Naples. It is true that the impresario Bustelli never staged his operas in Dresden, but he did acquire for himself a number of scores apparently never performed in Prague (Trionfo di Clelia, Antigono [not to be confused with Antigona]); these included an otherwise unknown Prolog oder Vorspiel and “various musical works consisting of parts of operas, arias, scores and nocturnes.” Friedrich Daniel Schubart also ranks Il Boemo alongside the famous composers Haydn, Gluck, and Vanhal, appreciating that his vocal music is “simple and penetrating, his arias and cavatinas are rich in new motifs, his recitatives are well-placed, and his choruses, powerful and heaven-shaking” (1784). Charles Burney, a music historian from that period, testifies to Mysliveček’s qualities, and Mysliveček also won the admiration of Mozart. His repeated invitations back to the court theatre of Naples are proof that he was a complete master of the style of that period in the genre called opera seria (dramma per musica), to which he devoted himself exclusively. Mysliveček’s own inventory of his works for Naples (1 October 1777) would seem to exclude the existence of two operas he is supposed to have written, Merope and Achille in Sciro. Even after his death, the Magazin der Musik (1784) expressed the opinion that in the opera L’Olimpiade (libretto: Metastasio; premiere 4 November 1778, Teatro San Carlo, Naples) he “…in many places surpassed the works with this same title by Sacchini and Pergolesi.”His productivity, his resourcefulness, his feel for style, his melodic invention, and his technical dexterity in operas, oratorios and instrumental works as well as his part in the stylistic development of the opera and the oratorio make Mysliveček one of the most important Czech composers of the eighteenth century.

Author: Stanislav Bohadlo

Nejposlouchanější

-

E. T. A. Hoffmann: Slečna ze Scudéry. Napínavý příběh dvojí existence jednoho pařížského zlatníka

-

Jak obstojí Lízinka na škole pro popravčí? Poslechněte si mrazivě černý román Katyně Pavla Kohouta

-

Tanec se slovy v rytmu jazzu. Oslavte s Vltavou 100 let Josefa Škvoreckého

-

Jack London: Tulák po hvězdách. Román o utrpení a svobodě bezmocného jedince odsouzeného na doživotí

E-shop Českého rozhlasu

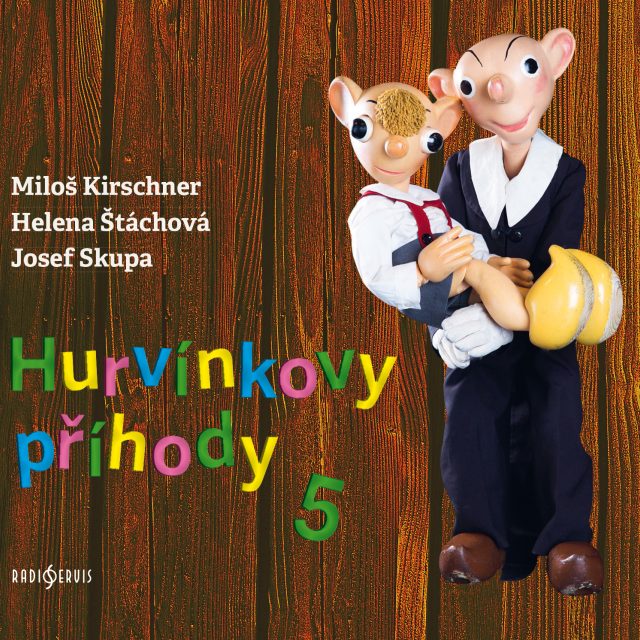

Hurvínek? A s poslední rozhlasovou nahrávkou Josefa Skupy? Teda taťuldo, to zírám...

Jan Kovařík, moderátor Českého rozhlasu Dvojka

Hurvínkovy příhody 5

„Raději malé uměníčko dobře, nežli velké špatně.“ Josef Skupa, zakladatel Divadla Spejbla a Hurvínka